Seeing Yourself Clearly

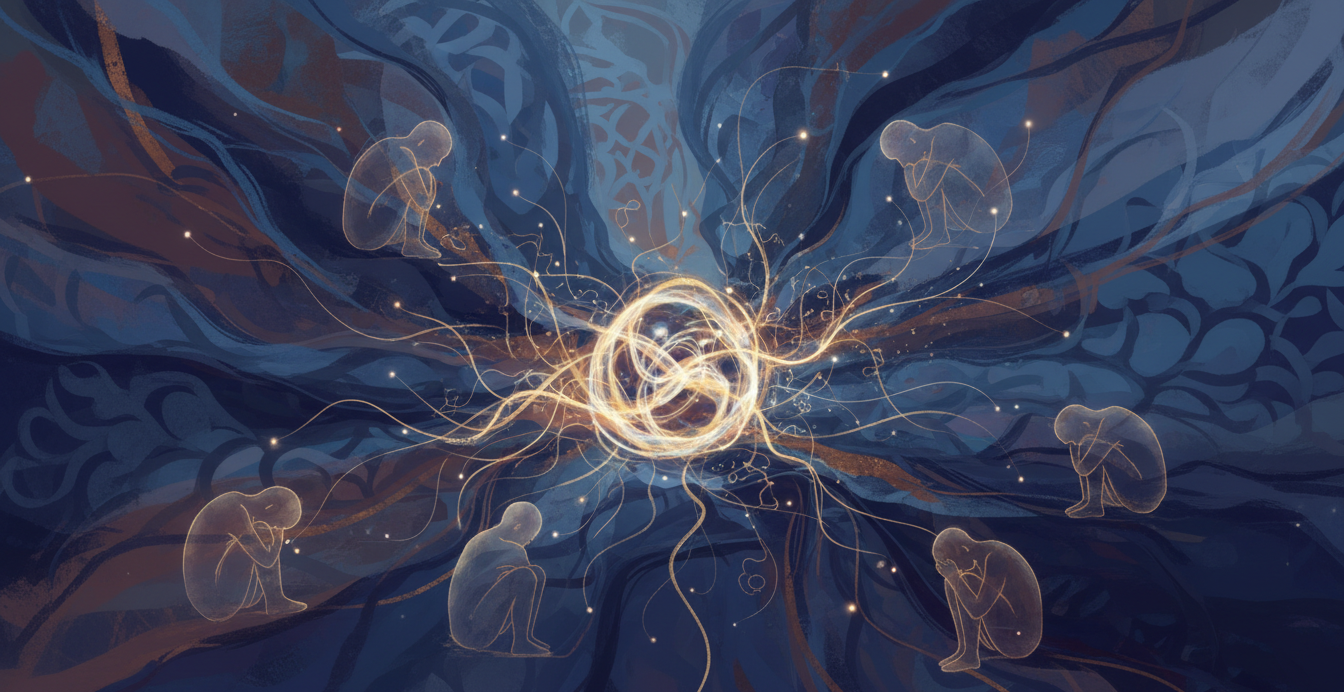

Self-Esteem, Self Image, and Belonging: A meditation with Virginia Woolf’s *Mrs. Dalloway

There is something quietly radical about Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf. No epic quest. No tidy redemption arc. Just a single day in London and a woman moving through it, feeling herself reflected and refracted by others. Woolf invites us into a truth we still struggle to name: self-esteem is rarely built in isolation. It is shaped in glances, silences, expectations, and the stories we tell ourselves while standing in a room full of people.

Mrs. Dalloway offers a mirror that is neither flattering nor cruel. It simply shows us how much effort it takes to feel “enough.”

The Invisible Arithmetic of Self-Worth

Clarissa Dalloway is socially accomplished, outwardly composed, and inwardly vigilant. She is constantly measuring. Not loudly. Not consciously. But persistently.

Am I doing this correctly?

Do I belong here?

Am I still pleasing, still relevant, still seen?

This is not vanity. It is vigilance.

Psychology and neuroscience now give language to what Woolf intuitively understood. The human brain is not merely social by preference. It is social by design. From an evolutionary perspective, belonging has always been tied to survival. Acceptance meant protection, resources, and continuity. Exclusion meant risk. The nervous system learned this lesson early and never forgot it.

Research on social evaluation shows that the brain processes social rejection using many of the same neural pathways as physical pain. Studies led by Naomi Eisenberger and Matthew Lieberman demonstrate that perceived exclusion activates the anterior cingulate cortex, a region involved in distress and threat detection. In other words, the brain does not treat social judgment as abstract. It treats it as consequential.

Clarissa’s constant self-monitoring reflects this biology. Her mind scans the room not out of ego, but out of attunement. Is the environment safe? Am I aligned with its expectations? Have I drifted too far from what is required to remain included?

Self-esteem, then, is not a static personality trait. It is a dynamic signal. Psychologist Mark Leary describes self-esteem as a “sociometer,” an internal gauge that tracks relational value and belonging. When social cues feel affirming, the signal rises. When cues suggest disapproval, invisibility, or misalignment, the signal drops.

Clarissa’s self-worth fluctuates accordingly. A glance. A memory. A perceived slight. A moment of recognition. Each one subtly recalibrates her internal sense of worth. This is not weakness. It is regulation.

Modern neuroscience adds another layer. The default mode network, the brain system active during self-referential thought, memory, and social comparison, is constantly integrating past experiences with present cues. This means that today’s interactions are never just about today. They echo earlier moments of belonging and exclusion, shaping how the self is evaluated in real time.

Clarissa’s interior life is full of these echoes. Who she was. Who she was expected to be. Who she fears she may no longer be.

Her self-worth lives in relationship to others because the brain itself is relational. So does ours.

When we frame self-esteem struggles as personal inadequacy, we miss the deeper truth. Much of what we experience as insecurity is the nervous system doing exactly what it was designed to do: monitor connection, anticipate risk, and protect belonging.

Woolf gives us permission to see this clearly. Not as pathology. Not as narcissism. But as the cost of being human in a world where worth has always been negotiated in the presence of others.

And perhaps the work, then, is not to silence the questions Clarissa carries, but to answer them with greater compassion, context, and care.

Body Image and the Performance of Acceptability

Clarissa’s awareness of her body is subtle, but persistent. Age. Fragility. Visibility. The body not as ornament, but as evidence. Proof that time passes. Proof that the standards against which women are measured rarely soften with it.

Woolf does not linger on mirrors, yet Clarissa feels herself reflected everywhere. In rooms. In glances. In memory. The body becomes a site of interpretation rather than inhabitation. Something assessed, rather than lived inside.

Psychology helps us name this experience. As early as the 1950s, Leon Festinger described social comparison as a fundamental human drive. We understand ourselves by measuring against others, especially in the absence of objective standards. The problem is not comparison itself. The problem is saturation.

Today, that awareness is amplified beyond anything Woolf could have imagined. Social media collapses time, space, and context into a continuous stream of curated bodies and edited lives. The brain receives an endless series of visual comparisons without the natural pauses that once allowed recalibration.

From a neuroscience perspective, this matters deeply. The brain’s threat and reward systems were never designed for this volume of input. Repeated exposure to idealized images activates the brain’s salience network, flagging what is “important” to pay attention to, while simultaneously engaging the default mode network, where self-referential evaluation lives. The result is not inspiration. It is self-surveillance.

Body image research shows that frequent appearance-based comparison is associated with increased anxiety, depressive symptoms, disordered eating, and diminished self-esteem. Importantly, these effects occur even when individuals consciously reject unrealistic standards. Knowing the image is filtered does not prevent the nervous system from responding.

This is because the nervous system does not evaluate fairness. It evaluates frequency. What we see most often becomes what the brain treats as normal.

Comparison fatigue, then, is not a failure of confidence or resilience. It is neural exhaustion. It is the cost of being repeatedly asked, “How do you measure up?” without ever being told that the ruler itself is unstable, commercialized, and designed to keep moving.

Woolf understood this exhaustion intuitively. Even in a pre-digital world, the pressure to appear acceptable required constant self-monitoring. Clothing, posture, expression, timing. Respectability was a performance with consequences.

Today, the mirrors multiply. Phones. Feeds. Metrics. Likes. The gaze is no longer occasional. It is ambient.

And the nervous system rarely gets a break.

What Clarissa reveals, across a single day, is something we now see across entire lifetimes. When the body becomes an object to be evaluated rather than a place to reside, self-esteem becomes fragile by design. Not because we are deficient, but because we are overstimulated by standards that were never meant to be met.

Perhaps the invitation here is not to opt out of comparison entirely, but to notice its cumulative toll. To recognize that fatigue is not personal failure. It is feedback.

And in that recognition, there may be the beginning of relief.

Perfectionism as a Survival Strategy

Clarissa’s perfectionism is quiet. It does not announce itself as striving or ambition. It appears as hospitality. As grace. As attention to the smallest details. The placement of flowers. The timing of arrivals. The smoothness of an evening that must not ripple.

But beneath this elegance is a familiar calculation: if I do this well enough, I will remain safe. I will remain included.

Perfectionism rarely begins as a desire to excel. It often begins as a strategy for belonging.

Contemporary psychology supports this reading. Research led by Paul Hewitt and Gordon Flett distinguishes between self-oriented perfectionism and socially prescribed perfectionism. The latter is driven by the belief that acceptance is conditional. That love, safety, or belonging depend on meeting external standards. Clarissa embodies this form. Her vigilance is relational, not narcissistic.

From a neuroscience perspective, perfectionism is tightly linked to threat regulation. When belonging feels uncertain, the brain shifts into a monitoring state. The amygdala heightens sensitivity to error. The prefrontal cortex becomes overengaged in planning, correcting, and anticipating outcomes. The body remains alert, even in moments meant for ease.

This is why perfectionism feels productive and exhausting at the same time.

Perfectionism often masquerades as care. As responsibility. As high standards. But beneath it is an anxious contract with the world. I will be flawless, and you will not abandon me.

Research consistently shows that chronic perfectionism is associated with higher rates of anxiety, depression, burnout, and emotional suppression. Importantly, it is not effort that causes harm. It is the belief that mistakes threaten connection.

Woolf captures the cost of this belief with devastating precision. Clarissa’s attention is split. She is present, yet never fully at rest. Her mind tracks reactions even as she hosts. Her nervous system scans for disruption even as she smiles.

Perfectionism keeps her vigilant instead of present. Polished instead of peaceful.

Modern neuroscience helps explain why. When the brain prioritizes threat avoidance, it sacrifices spontaneity, curiosity, and embodied pleasure. The parasympathetic nervous system, responsible for rest and connection, struggles to fully engage. The body remains subtly braced.

What looks like composure is often containment.

Woolf does not condemn Clarissa for this. She reveals it. She shows us that perfectionism is not a moral failing or a personality flaw. It is a learned adaptation to environments where belonging feels conditional.

And perhaps that is the most compassionate reframe of all.

If perfectionism is a survival strategy, then healing does not begin with lowering standards. It begins with restoring safety. With learning, slowly and repeatedly, that presence is not earned through performance.

That worth does not require polishing.

And that belonging does not demand perfection.

Belonging, Representation, and Mental Health Equity

Woolf does something else that feels quietly urgent today. She allows multiple interior worlds to exist side by side, equally real, rarely acknowledged. Consciousness does not belong to a single protagonist. It moves. It overlaps. It contradicts itself. And in doing so, Woolf makes a radical claim: inner experience matters, even when it is inconvenient.

This is most evident in Septimus Smith.

In Mrs. Dalloway, Septimus’s suffering unfolds in parallel to Clarissa’s social world, yet it remains largely unseen. His trauma does not announce itself in acceptable ways. It disrupts. It frightens. It refuses polish. As a result, it is dismissed, misunderstood, and ultimately abandoned by the systems meant to care for him.

Woolf was writing before the language of post-traumatic stress disorder existed, yet her portrayal aligns closely with what trauma science now confirms. Psychological trauma alters perception, memory, and emotional regulation. It reshapes the nervous system. Trauma is not simply something that happened. It is something that continues to happen inside the body.

Septimus’s pain is not invisible because it is minor. It is invisible because it does not conform.

Mental health research consistently shows that distress is more likely to be validated when it matches socially acceptable narratives. When suffering is articulate, productive, calm. When it can be explained without discomfort. When it does not challenge dominant norms around success, masculinity, race, gender, or emotional expression.

Septimus asks a question we are still answering imperfectly: whose pain is legible enough to be cared for?

Mental health equity begins here. With representation. With seeing varied interior lives reflected and taken seriously, not only those that resemble existing models of distress. Psychologists and public health researchers have long shown that marginalized communities face higher barriers to diagnosis, treatment, and compassionate care. Symptoms are often misinterpreted. Cultural context is ignored. Structural stressors are individualized.

Care becomes conditional.

Neuroscience reinforces why this matters. The experience of being believed and understood directly affects the nervous system’s capacity to regulate. Validation is not merely emotional. It is physiological. When inner experience is recognized, the brain shifts out of threat mode. When it is dismissed, the body remains braced.

Belonging, then, is not only social. It is psychological. It is the experience of having your internal reality acknowledged as real and worthy of care.

Woolf’s brilliance lies in refusing to rank inner lives. Clarissa’s reflections and Septimus’s anguish are not competing truths. They coexist. Both matter. The tragedy is not that Septimus suffers. It is that his suffering is not met.

This remains our unfinished work.

Mental health equity requires more than access. It requires curiosity. Cultural competence. Context-awareness. A willingness to ask not only what someone is experiencing, but what conditions shaped that experience.

To belong, psychologically, is to know that your inner life does not need translation to be taken seriously.

Woolf understood this long before policy frameworks and diagnostic manuals tried to catch up. She reminds us that the most radical act of care is not fixing, explaining, or smoothing discomfort.

It is witnessing.

And allowing what we see to matter.

Seeing Yourself Clearly

At the end of the day, Mrs. Dalloway is not about despair. It is about recognition. The courage to witness one’s own interior life without immediately trying to fix or perfect it.

Self-esteem grows not from relentless self-improvement, but from accurate self-perception. From learning to say: this is what it feels like to be me today. And that is enough to begin.

If this month asks anything of us, perhaps it is this:

To soften our self-talk.

To question the standards we’ve inherited.

To rest from comparison.

To widen the circle of whose mental health stories matter.

Woolf reminds us that clarity is not cruelty. Seeing yourself clearly is an act of belonging.

A gentle reflection to carry forward

When do you feel most yourself without performing?

What quiet standard are you still trying to meet?

And what might shift if you let your worth be something you inhabit, rather than prove?

Even here, there is a path.